When I first saw the movie “The Fellowship of the Ring,” I had some issues with the way they presented the great hall in Moria. Â The gigantic columns stretching out in all directions were nice to look at, but I found it hard to believe that such a thing could be built.

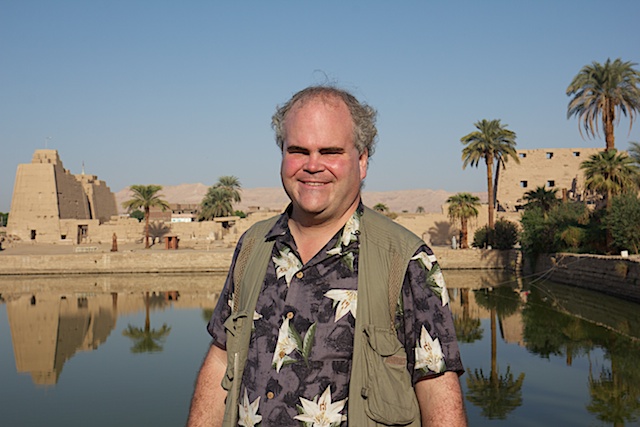

That was because I had never been to Karnak.

Karnak is the largest temple in Egypt. Â During Egypt’s golden age, it was the most important temple in the most important city to the most important god, Amun. Â Every pharaoh for a thousand years wanted to make his mark on Karnak, so he added a statue here, a line of sphinxes there, a chamber of columns in the middle of things, a couple of obelisks over in that corner. Â In some ways, it’s a bit of a mess. Â But it’s also overwhelmingly awesome.

Perhaps the most amazing part of the temple is the hypostyle, a hall full of columns laid out in a grid. Â 134 columns, 50-70 feet tall and perhaps ten feet in diameter. Â All it needed was orcs and a balrog and it would have been the great hall in Moria.

But the columns are not the only thing worth seeing at Karnak. Â Here’s a couple of scenes of Julie, one against the entrance to the temple, the other sitting in an odd stone niche.

Here’s a couple of scenes of obelisks. Â The first one is an obelisk to Tutmose III. Â It was originally one of a set of four. Â One of the others is in Central Park in New York; one is in London on the banks of the Thames. Â Those obelisks really get around.

That second one was built on the command of Hatshepsut, the female king. Â She apparently enjoyed erecting obelisks when she wasn’t presenting herself as a man. Â I’m thinking that Freud would have had a field day with this woman.

As I mentioned yesterday, Hatshepsut seized power from her husband’s male heir when he was but a boy. Â That boy grew up to be Tutmose III, the Napoleon of Egypt, a rather forceful character, and one who didn’t much like having his throne usurped. Â So after a twenty year reign, Hatshepsut disappeared from the scene. Â We don’t know how it happened. Â We do know that in the late years of Tutmose, her traces were erased across Egypt. Â Here’s an example of a relief that once featured her:

Note how the gods Horus and Thoth are showering a scratched out figure with ankhs (which represent life). Â That figure was once Hatshepsut.

Here’s some more miscellaneous statuary, some lovely hieroglyphs (which I’m starting to recognize: the bee and the plant with the semi-circles below mean “king of Upper and Lower Egypt”), Â and the holy pool used by the priests for ritual cleansing.

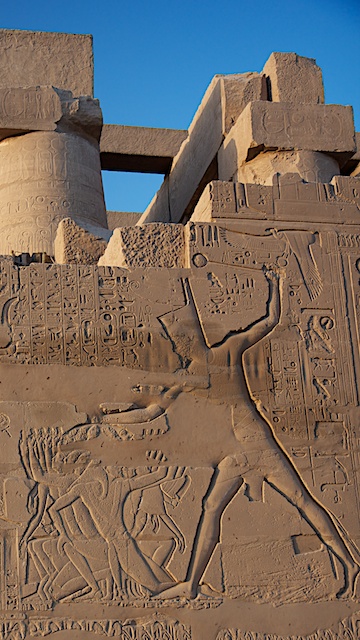

Here’s a bas relief of Rameses II. Â This is a traditional scene used to depict many kings smashing the skulls of their enemies. Â Rameses is frequently depicted in this manner: one starts to suspect that the man rather enjoyed bashing in heads.

In the funerary art in the kings’ tombs, they are often depicted as fighting demonic enemies on their trip through the underworld. Â Those enemies are often depicted as having no heads. Â Personally, if a king had bashed in my head, I would do my best to destroy him in the afterlife. Â No wonder they all have so many headless enemies when bashing in heads was apparently the royal sport of the pharaohs.

After the morning at Karnak, we didn’t have much scheduled for the rest of the day. Â We moved from the boat to a hotel and Julie and I wandered about Luxor a bit and watched sunset over the Nile.

But because we liked Karnak so much, Julie and I arranged to go to the light show that they have there. Â It was entertaining, informative, and cheesy: a lovely way to spend the evening. Â Here’s some pictures from under the lights.

Note that the above sphinxes, while possessing the traditional body of a lion, have the heads of rams. Â This is because they are at Karnak: Amun’s animal totem is the ram.